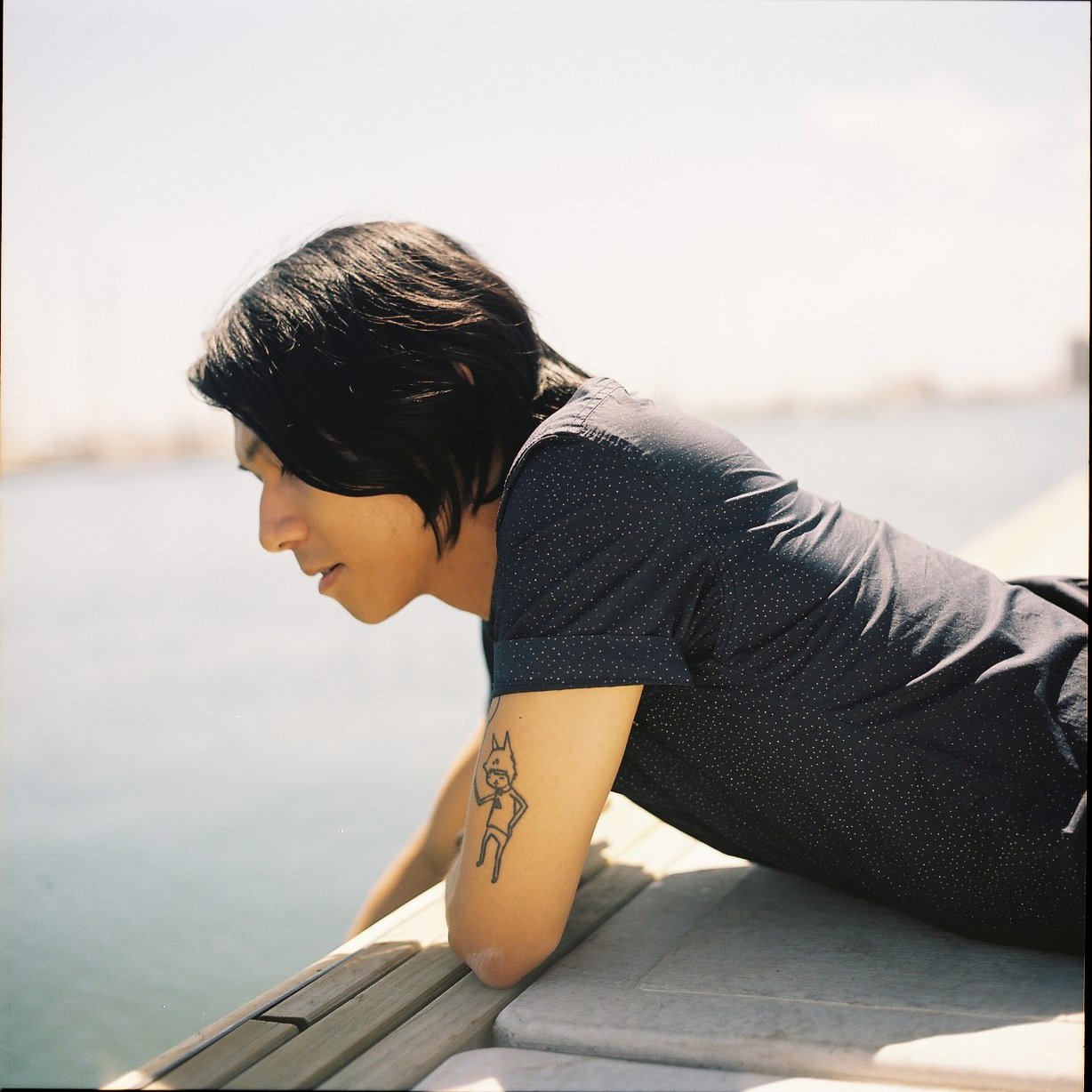

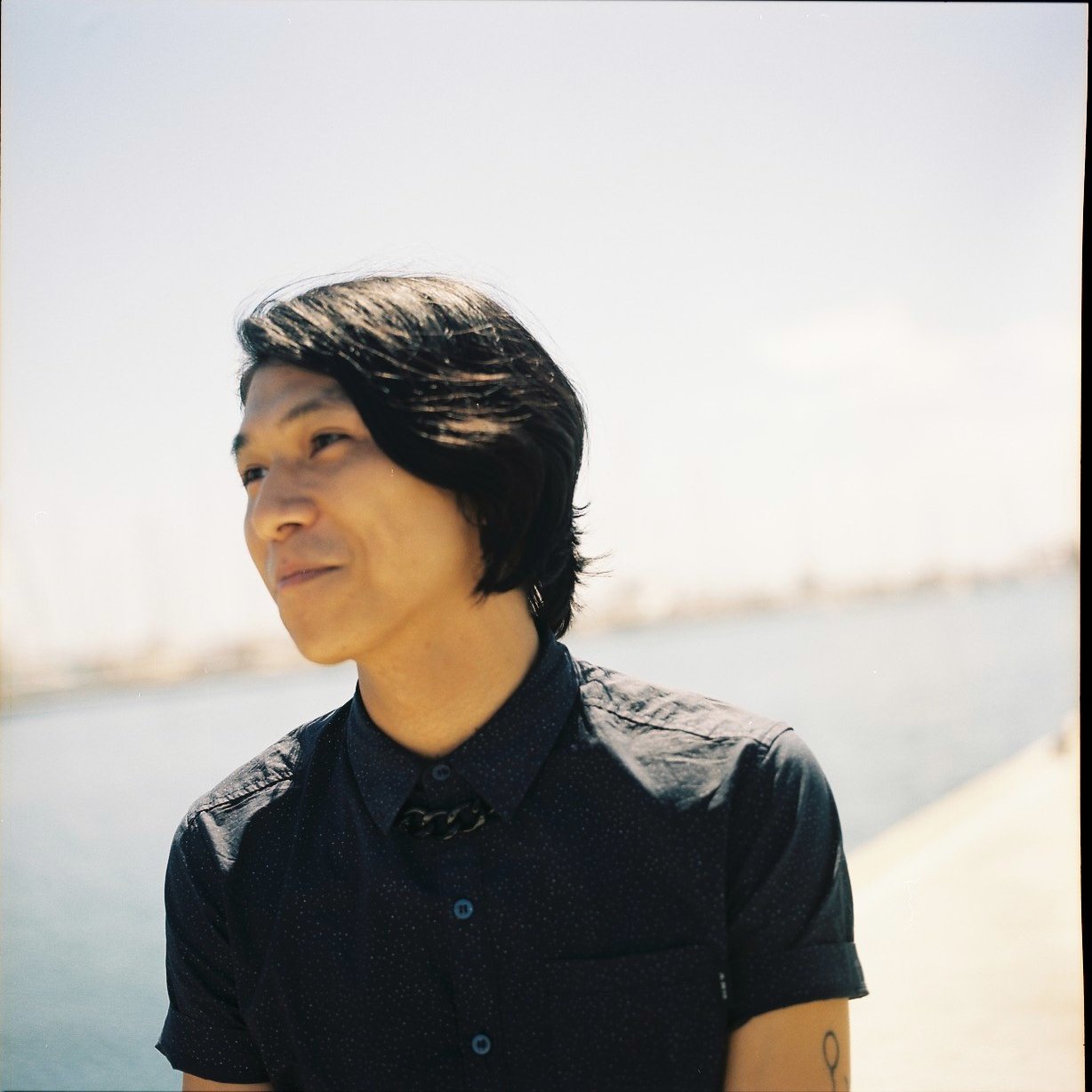

Interview #3 — Adolfo Aranjuez

Adolfo Aranjuez is the editor of Metro, Australia’s oldest film and media periodical. He is also the subeditor of Screen Education, a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. Named one of Melbourne Writers Festival’s ‘30 Under 30’ in 2015, Adolfo’s poetry and nonfiction have been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Scum, among others.

Adolfo spoke to Leah Jing McIntosh about his experience as an ‘invisible migrant’, navigating the Melbourne queer community, dance and mental health.

Find his poem, ‘Fingerprint’, here.

You have such an impressive trajectory— what has brought you to this point?

I’d known from the get-go that I was interested in publishing, but it definitely wasn’t my sole dream. I started an Arts/Science degree—I had aspirations of being a chemist of some description!—but dropped Science after semester one.

In late 2007, I began proofreading for Voiceworks and was inducted into the editorial committee several months later. It was a very rigorous, hands-on experience that served me well for the rest of my career; I dare say I gained everything I know about good editing practice from Voiceworks (shout-out to former editors Tom Rigby and Bel Monypenny). Then, in 2012, after she took on the editorship, darling Kat Muscat asked me to be deputy editor and I stayed on until I aged out at twenty-five.

Soon after graduation, I started working at Melbourne Books as an editorial assistant, and after six months was promoted to editor. I worked on various nonfiction manuscripts—from the history of Australian circus, to a monograph on ‘lost’ Australian modernist Michael O’Connell, to academic texts on landscape architecture—and curated the annual fiction and poetry anthology Award Winning Australian Writing.

After four years, I realised my passion didn’t lie in book publishing. There’s something about the quick turnaround of magazines: the finite parameters of a few-thousand-words-long piece that can be finished within a week; the more involved design process; the scope to tackle multiple topics at once. So I applied for the editorship of Metro. I’ve been here for almost four years now, and I feel like I’m in happy marriage: some ups, some downs, but generally stable and fulfilling.

What is your favourite edition of Metro you’ve edited?

I love all my babies, but it would have to be #186, Spring 2015: the queer issue. The theme came about circumstantially—magically, there were several queer Australian films out at the same time, and an author had pitched a hilarious ‘twenty-first birthday’-themed piece on The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. The issue tackled riveting topics like homonormativity, the problematic ‘universalisation’ of queer representation, the sidelining of bi and lesbian stories, and the general underrepresentation of LGBTQIA+ stories on Australian screens.

Aside from your illustrious editing career, you’re also quite a prolific writer.

Yeah, but for a long while, I didn’t feel comfortable calling myself a writer—I went with the descriptor ‘an editor who writes’—because I thought I didn’t have enough interesting things to say. I eventually realised that each of us possesses a specific voice that bears being heard. So I started training myself to be braver and writing more—and here we are.

In terms of nonfiction, I generally write medium-length and long-form stuff on minority politics (race representation, queer and gender issues, mental health, migration), film and pop-culture criticism, linguistics, education and philosophy, as well as the intersections between these topics.

My poetry is, weirdly, always about love—desire, loss, distance, yearning, crushing.

The rest of my freelance time is spent doing artistic bits and pieces—chairing and/or participating in panels, running workshops, judging writing competitions, performing spoken word…

Sometimes I find myself drowning. But I’m approaching thirty and I’d like to get to a point where my mid-life crisis (if I get one) isn’t because I didn’t do enough. Moments of recognition, like being one of MWF’s 30 Under 30, are incredibly wonderful and help keep me going. I wouldn’t have gotten to where I am without the support and love of so many people, and for that I’m very grateful.

You’re quite outspoken about mental health and it’s really exciting—not only is mental health stigmatised at large in Australia, but there is some evidence that it is often greatly stigmatised in Asian communities.

Totally. I think we all have a huge part to play in de-stigmatising and humanising mental health by making ourselves visible and ensuring our stories are told. People fear mental health, much like they fear most things they don’t understand. The difficulty is that a lot of what is already out there about mental health is either quite intimidating (too much jargon, too much moralising) or totally unconstructive (caricatures or reductive descriptions of serial killers or antisocial freaks).

I’m lucky in this respect because I’m ‘high-functioning’—so, while I’ve got bipolar-II, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and disorder (they’re different), panic attacks and subthreshold borderline personality disorder, I ‘pass’ as neurotypical, especially with the help of therapy and medication. I use that reality to remind people that some of us live with mental illness every goddamn day, and if someone high-functioning still has terrible periods, imagine what it must be like for people who have it worse—and who don’t have access to therapy and/or medication.

Growing up in the Philippines, I never heard anyone talk about mental health beyond ridicule and condescension. It’s only been the last few years that my parents are beginning to understand mental health’s implications. The prevailing view in the Philippines is still ‘just get over it’. That’s why we need to have these conversations; we need to dislodge these erroneous ideas about mental illness. Actionable large-scale change must begin with a change in perception/definition.

How has growing up in the Philippines impacted your experience in Australia?

I’m sort of an ‘invisible migrant’, in that I generally ‘pass’ as Australian-born, and people are often surprised that I immigrated at fifteen. I get the occasional microaggression, like people assuming that I should ‘just know’ things that happened here in the nineties, or that I do things ‘all Aussies’ do—both examples pretty innocuous, but still inadvertently presume a cultural homogeneity that Australia definitely doesn’t have.

The ‘Othering’ I experienced impacted me hugely. Adolescence is already such a pivotal—and difficult—time for self-growth, so as a migrant I was hell-bent on ‘assimilating’ super quickly. My parents didn’t move here with me (I lived with my older sister) so my coming of age was both unhealthily accelerated (I had to take on duties like rule-imposition, which we usually expect from parents) and stunted (I largely felt alone and perhaps didn’t get the necessary reassurance teens need during awkward phases).

My move to Australia was facilitated by my proficiency in English and early exposure to Western culture, thanks to American cultural imperialism in cosmopolitan Manila. However, a significant chasm developed between me and my origins. I’d drifted apart from my parents—I found it super hard continually having to explain things from my ‘new culture’. I was disconnected from the diaspora—I was hugely ashamed of being Filipino up until I was about twenty and evaded admitting I wasn’t born here to draw attention away from my ‘difference’.

You recently spoke on this panel discussing the state of LGBTQIA+ rights and representation in Australia. Can you speak to your experience as a queer person of colour in Melbourne?

Generally speaking, it’s hard not being a white, masc gay cis-male. I’ve previously written about homonormativity in queer communities, and took part in a roundtable of queer POCs which was published in Plaything magazine.

I’ve luckily evaded overt bigotry in my sex/dating life thus far—likely because of my vague racial appearance and I’m well ‘assimilated’ (terrible but true)—but the gay male ‘scene’ is pretty homogenous in the grand scheme of things. To be honest, I find it rather alienating—so much so that I’m increasingly disavowing the label ‘gay’ (which rests on a reductive, cis-privileging, binaristic notion of gender) for myself, opting for the more inclusive ‘queer’.

Some gay-identifying men are pretty misogynist and, worse, feel they’re exempt from accusations of sexism because they’re not attracted to, and therefore apparently can’t objectify, women. It’s all pretty damning, really. And it’s a truism that there’s systemic racism among Australian gay men, who connect whiteness with masculinity and desirability.

Anyway, despite all that, there’s a lovely community of Melbourne queers that I love, with heaps of POCs represented. This specific pocket of the queer world is what I want the majority of it to be, but we’re not quite there yet. I suppose there’s still a disjuncture between ‘official’, mainstream, homonormative queer spaces and more inclusive ‘underground’ ones. The existence of both is reassuring and positive, of course, because they show that our society welcomes diversity, but I’d like to see more overlap—especially given the immense privilege of the former. I recently went to see the Melbourne chapter of UK queer-POC cabaret event The Cocoa Butter Club and, holy fuck, we need more of this stuff in Australia.

We’ve seen you venture into dance in two of your most recent performances. Have you always been a dancer?

In primary school, I used to do dancing and cheerleading but I couldn’t continue after I immigrated to Australia because logistics didn’t allow me to. What led me to reconnect with dance were two enormous upheavals in my life in 2015: I went through a really bad breakup and then, a few months later, my best friend Kat died by suicide. I can’t begin to articulate how potent those two losses were—but it was like life grabbed me by the shoulders and shook me into doing more things that I loved.

Could you elaborate on the relationship between dance and your experience of mental health?

A significant part of dance is learning to become comfortable with ‘sitting into’ movements: letting your muscles contract, create tension and release; allowing yourself to flow and pause with the music; respectfully drawing the choreography’s lines and shapes with your body. My psych talks about ‘sitting in’ emotions—of letting them fill you up then wash over you; I love the resonance between the two ideas.

It’s only really in the last few years that I feel I’ve started embracing the person I want to be. Beyond the obvious enjoyment I get out of it, dance, for me, is about mastery and challenging myself to improve. My life thus far has centred on the cognitive, the verbal; dance allows me to complement that with the kinaesthetic and the physical. I’ve learnt so many life lessons from dance, too: the need to ‘fight for’ steps when they, at first, don’t feel natural, but also to not ‘fight with’ the expression—to listen to the music and wait for the right time, to find the best flow, to breathe.

Is your unique combination of spoken word and dancing an overt blurring of genres, a response to your experience of intersecting cultures – perhaps a kind of artistic ‘third space’.

Undoubtedly—it’s a powerful way for me to take from the raw material of my experiences and carve out my own form of expression. But it’s less a result of racial Othering or interstitiality, and more an inability of the ‘verbal arts’ to provide a comprehensive medium for expression. I already grapple with this as someone bilingual (oh, the many Tagalog phrases I fail to translate to English!), but words will never fully account for the dynamics of emotion, romance, sensuality. Or maybe it’s just me—I try but fail—but there are cases when it’s so much easier with movement. I mean, dance is its own language.

Tell me about this language.

Dance’s vocabulary isn’t as rigid or restrictive or exclusionary as verbal language. Inbuilt into words is the notion of correctness—you’re limited by syntax; you need to grapple with grammars. There’s also a conservatism at the heart of literature; there are only so many ways you can take licence with language and, even if you push conventions, you’re still expected to fall in line with convention lest your work be dismissed for being gimmicky or sentimental or failing institutional expectations.

Dance—at least, the genres I do: hip-hop, urban, commercial, dancehall—is very open to modification: you build on choreography and make it your own. These genres are rooted in racial and class-based marginalisation, and they’re inherently catholic; contrary to something like ballet (which is beautiful and full of technical brilliance, but also so, so elitist and, in many sectors, quite racist), the eclecticism of these dance styles allows people to just ‘do’ them without fear of exclusion or not doing it ‘right’.

I attend dance class at least twice a week; there, people of various levels and from various backgrounds come together, and you’ll often hear advice like, ‘If you make a mistake, make it epic’—an incredibly empowering line if there ever was one. You wouldn’t really hear that in Melbourne literary circles, and I think partly holds back Australian lit culture: we’re sometimes so driven by definition, so focused on highlighting our status as ‘literati’, so critical and consumed by envy and ego that we often forget that our role as intellectuals shouldn’t eclipse our existence as artists.

How might we understand art, instead?

Art, in my view, is fundamentally about connection and empathy; writers sometimes lose that in our race to amass publication credits and panel appearances. But the dancers I’ve met aren’t like that; I can’t tell you how many dancers—even those who are world-renowned and brilliant—encourage you to ‘just dance it out’ with them.

Do you have any advice for young editors?

With editing, it’s worth remembering that it’s not a power-tripping exercise; a good editor doesn’t get smug about other people’s apparent language inadequacies. While editing skills and concepts can be easy to pick up, there are also fundamental attributes or propensities—tact and diplomacy being two big ones— that are harder to learn, often inextricable from your personality.

Also, like any other industry, publishing is about who you know. Writerly folk are naturally interested in building and maintaining relationships, so it’s also a great idea to come to industry events like open proofreading callouts, writers’ festivals and book launches to show that you live the industry that you purport to be interested in.

And read. A lot. Always be open to learning more.

What are you currently reading?

Flat Exit, a poetry collection by Broede Carmody; the latest issue of The Lifted Brow; various essays and articles on reification, symbolic violence and ‘vicious abstractionism’ as research for a big forthcoming essay for Right Now.

What are you currently listening to?

I’m listening to a lot of R&B at the moment—stuff that’s really good to dance to, songs by Kehlani, Rihanna, NAO, Syd, Tinashe—but also poppier things with killer beats and basslines, like Zara Larsson and Ariana Grande. Hey, they’re all women (fuck yes)!

I’m also *whispers* enamoured of the many Top 40 songs with Caribbean/dancehall/reggaeton flavours because I’m clearly not invulnerable to trends (damn you, Ed Sheeran ‘Shape of You’!).

What does being Asian-Australian mean to you?

To me, it means living dualities—being both self and Other, kicking normative notions of assimilation and homogeneity in the keister. It’s speaking English flawlessly with an Australian(ised) accent but phoning your sister and breaking into accented Taglish. It’s having a boy stay over after a date and feeling giddy that he has to rush off to brunch so you can have garlic rice on your own for breakfast. It’s quickly changing out of your ‘house clothes’ to go to the shops. It’s Footscray and St Albans and Dandenong. It’s knowing that Pauline Hanson is wrong. It’s bravery and resilience and quietly fighting to dismantle stereotypes and shame and silencing.

Find out more

Interview & photographs by Leah Jing McIntosh