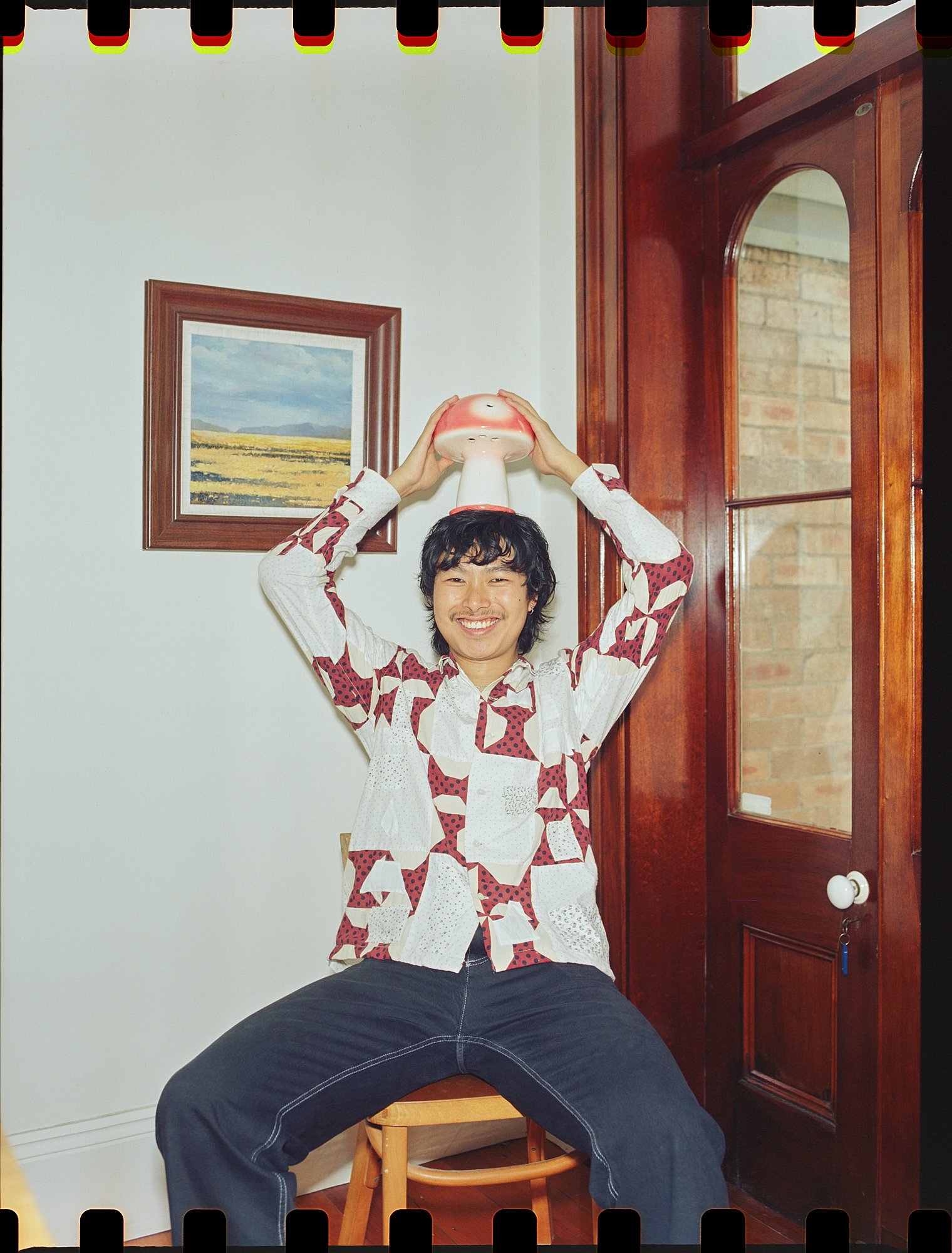

Interview #213 — Michael Sun

by Claire Cao

Michael Sun is a critic and essayist. He currently works in culture and lifestyle at The Guardian, and he has contributed film and music writing to The Saturday Paper, The Monthly, Sydney Review of Books, ABC Arts, Australian Book Review, and many more.

He designs posters for parties, friends, lovers, and enemies, and he hosts a weekly show on FBi Radio in Sydney, where he lives.

Michael spoke to Claire about mid-2000s movies, narrativising your own life, book signalling, and rodents.

What did you read and watch growing up that is (fortunately or unfortunately) a formative part of your personality?

Claire, you know that I talk about my teenage love affair with the extremely twee rom-com (500) Days of Summer at any given opportunity, so instead I will take this chance to reveal another embarrassing fixation: The Rules of Attraction, both the film and the Bret Easton Ellis novel from which it was adapted. I’m saying this because I recently rewatched the film, which was released in 2002 and starred a depressingly ripped James Van Der Beek alongside Ian Somerhalder as a cruel, affected twink.

I first encountered it late at night—probably on a 3” iPod screen—as a scrawny and deeply unworldly 12-year-old. The film loops back on itself, replaying the same moments from a trio of perspectives—it’s crass, beautiful, and at times completely, insanely earnest. It’s full of college students averring their love for each other and taking drastic actions to prove it. Not to sound too lewd, but I could feel myself expanding when I first watched it; I thought I could touch God. I bought the book with whatever savings I had the next day.

Like any other teenage poseur, I was a Bret Easton Ellis groupie all throughout high school, much to the chagrin of my English teachers. In an interview for a university scholarship, they asked me what I was reading and I proudly pulled out a copy of American Psycho that I had brought in case they asked me what I was reading. I didn’t get the scholarship, for unrelated reasons. I’m glad I had the experience, because most people don’t have the honour of seeing their heroes get cancelled. Watching Bret Easton Ellis go up in a blaze of glory was humbling, in a way. A reminder of our own impending demises.

Ellis’ work really lived and died in that pre-millennium bubble; meanwhile, you grew up in a time where the internet transformed more rapidly than ever. In your design work, I am struck by how you entwine retro, so-called ‘ugly’ internet imagery with newer techniques and aesthetics. How has the evolution of the web influenced you over the years?

It sounds mawkish, but I am constantly thinking about the early internet; everything about me is a product of growing up with unsupervised computer access. (My parents eventually installed internet filters when I was 16, but by then the damage had already been done.) There’s a writer I love called Paul McAdory who wrote a column for the now—sadly—defunct Astra Magazine. It was called ‘Show Me Your Hole’ and it was about his search for a ‘determinative wound’: the singular trauma, however petty, from which all other neuroses stem. If I had a determinative wound, it would be the summer I spent feverishly clicking through a website called ExitReality, which billed itself as a virtual reality experience like Second Life but in actuality hewed closer to an abandoned mall. A liminal space, if you will (sorry). You could make avatars and roam around a vast, empty space drenched in permanent sunset; you could click around for miles and not see a single other user, presumably because the site was still in its beta phases, so I have no clue how I discovered it in the first place.

After many hours of meeting no-one on ExitReality, I crash-landed into another avatar while absent-mindedly spamming the keyboard. In a very buggy chat system, he said his name was Tommy, he was 19, and he was from Illinois. I was a closeted tween in Sydney, Australia, so naturally I said I was a 17-year-old senior from Ottawa—this happened during a phase in my life where I had an unhealthy obsession with moving to Canada, even though I didn’t know the first thing about French people or ice hockey. We added each other on MSN, and I would search Wikipedia feverishly for Ottawa facts to repeat to him while he regaled me with his love of Death Cab for Cutie and his mother’s cookie recipes. I told him Transatlanticism was my favourite album (a lie) and that I wished he could mail me cookies (a truth). I’m not sure how we fell out of contact but when we did it was devastating, pulverising. I’ve been trying to bottle the rush of that encounter ever since, to answer your question very circuitously.

Our friend once said that you socially engineer our conversations to inevitably be about ‘some random actor from a 2012 movie’. I’ve noticed in your writing that you are drawn towards the (on-screen and off-screen) personas actors cultivate, as well as indie film from the 2010s. Can you explain these fixations?

I think the right performance is transformative—not in the cheap sense of an actor transforming themselves for a role, but that sometimes a performance is so blinding, so brilliant, that I have no choice but to shift my entire universe to match that energy accordingly. This is mostly because I am melodramatic and prone to hyperbole. But also—for better or for worse, probably worse—I have always narrativised my own life, which means I see film and acting as a means to understand the world around me. I often find the things I do or the choices I make completely opaque until I see similar events and/or motivations on screen—that usually results in a lightbulb moment which brings me suddenly closer to finding some glimmer of order amidst the murky chaos of existence. I know it sounds grotesque. Call it main character syndrome.

On another level, I grew up very enmeshed within stan cultures—anyone who has known me for more than five minutes will have sat through my lengthy screed on the Vampire Weekend fandom, which operated at one point on Twitter and left a gaping, loafer-shaped hole in my heart once it imploded in the mid-2010s. So I guess I am instinctively drawn to obsession. There’s a Caroline Polachek song (‘Blood and Butter’) where she serenades a lover by saying she wants to ‘dive through your face to the sweetest kind of pain’. It’s such a carnal image which I think also applies to stan cultures, the way you want to embody someone so completely that you lose sight of who you once were. The most recent performance I can remember that changed me in this way was Tilda Swinton’s performance in Memoria. She plays a wandering expat in Colombia who hears an intermittent whomp in her mind with no tangible source. She is cool to the touch, entirely reflective, any perturbance sublimated underneath a laconic ease. It felt aspirational—when I witnessed that, it made me wish I was more enigmatic.

Trust me, your brain is plenty enigmatic. There’s such a unique eclecticism to your thinking that always stuns me, where you create unexpected connections between high and low culture, the old and the new, the niche and the mainstream. Speaking of Vampire Weekend, your style occasionally reminds me of frontman Ezra Koenig’s old blog INTERNET VIBES—where he examined everything from Wellington boots and the Angkor Wat and, somehow, there was perfect emotional cohesion. Do these types of sense-memories and connections come naturally to you?

They do come naturally to me, but only insofar as everyone in my life is gracious enough to abide by my chaos and my stubbornness. There’s that old trick they teach you in media school where if you’re ever interviewing someone, you’re supposed to stretch silences out for awkward periods of time in the hopes that the other person will eventually fill the space with something new or unguarded. The same thing happens in any conversation I am in—if you leave 0.5 seconds of silence, I will, intentionally or otherwise, say something insane. I can’t help it; it’s a compulsion.

This also occurs when I’m writing: once I surpass the enormous, agonising hurdle of actually starting—which, of course, seems increasingly impossible with every deadline—I find myself remembering tidbits of information I had long suppressed. It’s mostly detritus from the media I consumed as a teenager, or a tweet I found funny nine months ago that suddenly comes rushing to the fore—but sometimes, just sometimes, it’s relevant enough to worm its way into a piece. That’s the chaotic part.

Then there’s the stubbornness. I have been labelled many things—annoying’ is probably most accurate—but I refuse to watch, listen to, or read anything I instinctively feel I’m not going to like. If a friend puts on a movie and I’m not into it within five minutes, I will literally stand up and leave. It’s not that I think my taste is untouchable or superior in any way—I don’t. I’m just so deeply afraid of boredom that I spend an inordinate amount of energy and brain power on predicting what is going to excite me, and what is going to leave me cold. It means I sometimes miss out on art that I later love. I refused to watch Succession, for example, until its penultimate season, and then I ate my words and had to do a prolonged apology tour to everyone I’d jilted.

You write frequently about Internet trends (like the BeReal craze and habit tracking apps). I was wondering if you could talk about your process with approaching these pieces, and how that approach has changed, especially as online spaces have evolved and become increasingly siloed?

I’m sorry to contradict my entire last answer, but I feel like the internet is maybe the last place where I’m not thinking about whether or not I will like something before I consume it; online, I’m hardly thinking at all. I’m a lot more permeable to online ephemera than any other form of media. If there are any scammers out there reading this, please stop now: I’d consider myself much more gullible than the average internet user.

Online, my motto is essentially: try anything once. Which, because I’m a deeply captious person, means that I’m constantly complaining about the things I try. It doesn’t quite make sense—even to me—why I’m constantly trying new internet trends if I hate all of them equally. The only answer I can give is this: masochism. It’s a lucky turn of events that I’m able to sometimes channel that contrarianism into writing, and I’m very grateful to my editors for providing a home for my unbridled cynicism.

Whenever I write a piece about an internet trend, I scroll for hours and take pages and pages of notes; there is an extensive notes app document on my phone which just says things like ‘corecore’, ‘raw carrot salad’, ‘making jelly’ and ‘Apple TV speedrun’. Most of these words no longer make sense to me; I harbour the secret fantasy of anthropologists hundreds of years from now discovering this list and deeming it a sacred religious document. The major way in which my approach has changed is that I joined TikTok (with much reluctance) about six months ago, after many years of decrying it as the worst platform with base ideals and gaudy imagery. I believe my exact words were: ‘I do not exist in video form!!!!!!!’ (See above: stubbornness.)

There was a period where I could get away with ignoring the existence of TikTok and learning all I needed about its particular strain of insanity via other mediums: reading the work of fellow internet reporters, or—god forbid—reshares on Twitter and Instagram. It’s harder to avoid now, though—TikTok use has sped up at such an exponential rate that even vocalising its velocity seems trite. So it’s basically forced me to join its little hivemind if I want to continue writing about internet culture. I will detest it forever, though: everything about TikTok is so toweringly tasteless; an ouroboros of grotesqueries. To borrow from André Leon Talley: we are living in a famine of beauty!

In one of my favourite pieces of yours, ‘no thoughts head empty’, you say something so controversial but brave: that many of us care more about signalling we are reading than actually reading. What is your relationship to reading now?

Unfortunately I will be a book signaller forever; there is something so coquettish about paging through the right book in front of the right person. I consider it a form of flirtation, platonic or otherwise. A devastating thing happened to me recently: I was reading Hua Hsu’s Stay True and I somehow managed to lose the cover jacket. To the passing eye, it probably looked like I was reading some vintage hardback like a 2011 hipster. Either that or I was perceived as Joe Goldberg in You, which are two of the worst possible associations I can imagine.

I’ve always admired the way you interweave critical observations with searing personal interludes. For example, you analyse ‘suburbia’s assimilatory power’ in The Virgin Suicides, and link it to your own parents’ migration. Is personal experience a critical part of your writing practice, and—when it comes to a medium such as criticism—how do you balance it with writing for an audience?

My thoughts on this have changed in years since that essay was published. While I still stand by it, the context in which I wrote it (while losing my mind in isolation at my parents’ house) certainly informed how much of my personal life I included in the piece. I was literally spending 12 hours a day doing insane things like re-reading all my old text messages and staring into the sun and scouring childhood photo albums for evidence. Evidence of what, exactly, I still have no clue to this day. But I was on my hands and knees next to my parents’ cupboard flipping through film print-outs until my brain and feet were numb.

I’m not so sure anymore that memoir and criticism can—or should—be fused. Or perhaps what I mean is that when it’s done ineffectually, which it so often is, the memoir element gets mistaken as shorthand for something more profound, when really our personal lives don’t always hold the significance we might ascribe to them. There are exceptions to the sludge—such as Hua Hsu, obviously, whose prose is so limpid that there’s no way of envisioning his memoir without its digressions into criticism. Other times, though, I’ll be reading a review or an essay, and I’ll think to myself: please hurry up, I don’t need to know about that time you slipped and fell on the playground to understand your relationship to this film. It just feels so … blinkered. I’m not blameless however—there have been many times I have leaned on personal anecdote as a crutch. But I think it’s lazy. We should do—and demand—better.

Where do you see yourself headed in terms of what kind of art you're drawn to and what kind you seek to make?

Most of what I consume on a daily basis is criticism. Right now, I’m very drawn to contemporary critics who double as meticulous sentence stylists. I know not everyone reads reviews for their prose, but I think even the worst opinions can be forgiven by great sentences; on the contrary, the most insightful reading can be rendered soupy by bad phrasing. I’m often re-reading reviews and essays by Melissa Anderson, Cat Zhang, David Ehrlich, Phoebe Chen. Sorry to be hideously earnest, but I would love to pull off even a mote of their stylistic brilliance.

You’ve described both Sid the Sloth from Ice Age (2002) and the rat from Flushed Away (2006) as your ideal men. But I have to know: who do you think would make the better partner and why?

First of all, the rat from Flushed Away has a name and it is Roddy St. James, which sounds like a Matthew Macfadyen character. My serious answer: Roddy and Sid are basically the beastly equivalents of James Van Der Beek and Ian Somehalder in The Rules of Attraction, stripped of any worldly etiquette to reveal their tawdriest instincts. Underneath that impeccable tux, I’m sure Roddy is depressingly ripped; Sid, meanwhile, is a cruel and affected twink. Of those two categories, there’s only one I trust. It’s Roddy all the way.

Do you have any advice for emerging designers and writers?

Be critical—of your own work and others’ work. ‘En vogue’ isn’t a synonym for ‘good’.

Who are you inspired by?

My friends. You!

What are you listening to?

I often get sucked into these vortices of listening to one song on repeat for days, which is maddening for everyone around me and deeply satisfying to some elusive part of my brain. Right now it’s ‘Crush’ by Ethel Cain.

What are you reading?

With sincere apologies to my book club, whose monthly pick I am shirking for the fourth time in a row, I have finally cracked open my copy of Nick Pinkerton’s book-length essay on Goodbye, Dragon Inn (dir. Tsai Ming-liang, 2003). Mostly because I am haunted by the image of Claire Denis—the urtext of all book signallers—reading it.

How do you practice self-care?

By screaming.

What does being Asian-Australian mean to you?

Having five group chats on the go at any one time, each supplying a distinct and steady stream of dirt. Gossip is solidarity!

Find out more

Interview by Claire Cao

Photographs by Ted Min